With modern aircraft continuing to increase in size, and weighing hundreds of tons — unlike your car — parking an aircraft is not as simple as pulling into a spot and turning off the engine.

The largest passenger aircraft in use — the Airbus A380 — has a wingspan of nearly 80 meters! Aside, from the sheer size of the wings, the placement of the cockpit also means that for most longhaul aircraft airline pilots cannot see the wings at all.

Pilots of large commercial airliners have the daunting task of parking these behemoth aircraft safely and efficiently at the airport gate. So, how do pilots park these aircraft correctly, without hitting anything?!

In this article, we’ll walk you through how pilots steer the aircraft onto stand, what they look out for during the parking process, and why it’s such a big deal if they get it wrong!

How aircraft turn onto stand

When most people think of steering aircraft on the ground, they think of the pilots using the rudder pedals:

The second method for turning large aircraft is by using the tiller. The tiller is a small yolk shaped wheel that can be thought of as a small steering wheel.

In older aircraft, tillers were only located on the captain’s side of the cockpit — co-pilots were not allowed to taxi the aircraft! — but in most modern aircraft there are two identical tillers on each side, used for sharper turns during ground manoeuvring, such as parking.

Unlike the rudder-linked steering, aircraft tillers typically control the nose wheel of the aircraft up to ± 140 degrees. This means that pilots can make sharp 90 degree turns onto stand, and it also allows the pilots to make small, precise adjustments to the aircraft’s position to accurately guide the aircraft into the correct parking position.

Over the years, commercial aircraft have dramatically increased in size. As a result, airline pilots can no longer see the wings, and are unable to judge if they will fit through gaps.

So, how do they find the parking stand without hitting anything?

Pilots know they are taxiing on the centreline by having the correct visual picture in the cockpit. This is usually a marking or windowpane that the pilots visualise the centreline running through. However, in the newest and largest aircraft, such as the Boeing 777-300ER, pilots also have access to aircraft landing gear camera systems, more accurately showing the centre of the taxiways — similar to parking cameras in cars!

Aircraft parking guidance systems

Following a centreline is accurate enough for taxiing to the parking stand, but in a confined environment of individual aircraft stands — with jetty’s, steps and ground equipment nearby — more accuracy is required.

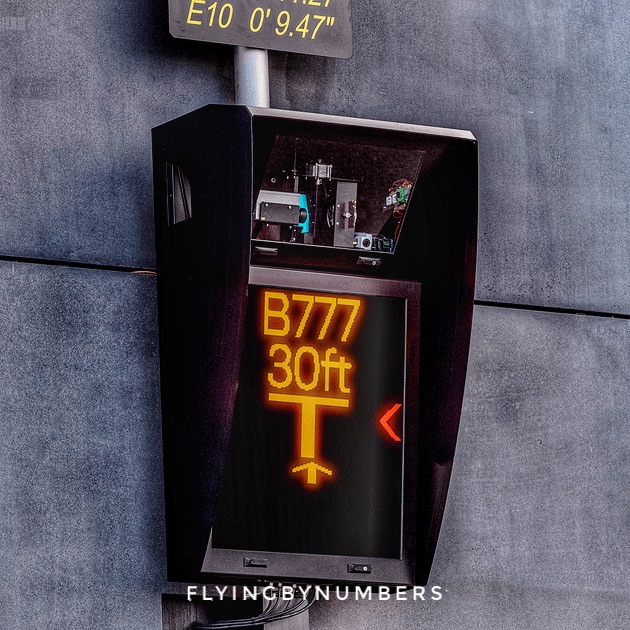

Having made the initial turn onto stand, pilots will transition to using systems known as A-VDGS — advanced visual docking guidance systems.

These docking guidance systems are a valuable aid to pilots, providing visual cues and directional signals to help guide the aircraft into the correct parking position.

Before turning onto the parking stand, ground personnel will check that any remaining equipment is moved into specified locations, and will select the specific aircraft type that is about to park.

Pilots will check that the guidance system has been correctly set for their aircraft model — such as the Boeing 777 pictured above — then begin following the directional signals. Advanced guidance systems are calibrated to aircraft sizes, and work by detecting the nose of the aircraft and the tailplane. Digital screens display how far the aircraft needs to taxi forward to reach the perfect parking position, and show aircraft deviation left or right from the centreline.

Why planes can’t reverse!

Despite the assistance, parking a large aircraft requires skill and precision, as planes are not easily moved if they accidentally stray too far from the ideal parking position.

A frequent question asked, can planes reverse? Technically, the answer is yes.

Although aircraft do not have power to the wheels — relying solely on the thrust from their jet engines to move on the ground and in the air — this thrust can be directed forwards. Known as reverse thrust, this technique is commonly used to help the aircraft slow down on the runway and to save brake wear.

So, why can’t they use this to reverse? Well, they can! But it’s prohibited in virtually all operators worldwide. The reason for this is twofold:

- Pilots cannot see behind the aircraft, even the latest aircraft fitted with cockpit cameras only look directly down at the landing gear.

- It would require a huge amount of thrust to move heavy aircraft around, and would potentially cause huge amounts of debris and damage to anyone in front of the aircraft!

So, as planes aren’t equipped with reverse gear, it is imperative for the pilot to get it right the first time. Jetties, used for passenger disembarkation, have a limited range of movement and will not be able to be correctly attached to the aircraft unless it is parked in exactly the right spot.

Pilots do occasionally get the parking manoeuvre wrong, and this requires shutting the aircraft down, calling for a ground tug, and towing the aircraft backwards to the correct position. At a busy airport, arranging this can take significant amounts of time — and is involves a very embarrassing explanation to the passengers as to why they cannot disembark!

Summary

While parking an aircraft may seem straightforward, there are numerous factors that pilots must consider, such as taxiway size restrictions, aircraft weight distribution, and the surrounding aircraft and ground equipment. As a result, parking an aircraft is a complex and critical task that requires the pilot’s full attention and skill.

Many airfields assist pilots in parking accurately by providing modern aircraft guidance docking systems, which track the aircraft position, and depict the aircraft’s realtime position on a digital screen for the pilots to follow. Pilots guide the plane into position using the tiller, not the rudder pedals, as it provides more accurate control.

It’s crucial to get the parking manoeuvre right because aircraft cannot reverse. Backing up and trying again is not an option. While technically reverse thrust can be used to move backwards, the lack of visibility and high thrust required means it is considered too dangerous and prohibited by virtually all airlines.