When you’re flying as a passenger on a commercial airliner, it’s hard to imagine the level of coordination and planning that goes into ensuring your flight is safe. As this coordination is largely behind the scenes, airline pilots and flight attendants frequently hear questions from worried customers regarding flying too close to other aircraft!

”Can I go and speak to the pilots because I think we nearly collided with another plane”?

In reality, any crossing aircraft is likely to be significantly further away than it might appear, and is perfectly safe!

So if you’re a nervous flyer, think your plane got too close to the one in front, or are simply curious, in this article we hope to provide some reassurance.

By the end of the article, you’ll know:

We’ll explore how pilots avoid crashing into other planes, using both old-fashioned and modern methods. And remember, because of these rigorous safety nets, there are virtually no mid-air collisions between modern commercial aircraft.

Nervous flyers, take note, the risk of dying in a mid-air collision is simply too small to calculate!

How pilots avoid planes: The old-fashioned way!

There’s a lot of fancy technology in modern airliners, but despite all the advancements, some key rules pilots have followed for decades remain unchanged.

Two key methods of maintaining aircraft separation are the north-south rule during the cruise, and following procedural methods after takeoff and during approach to landing.

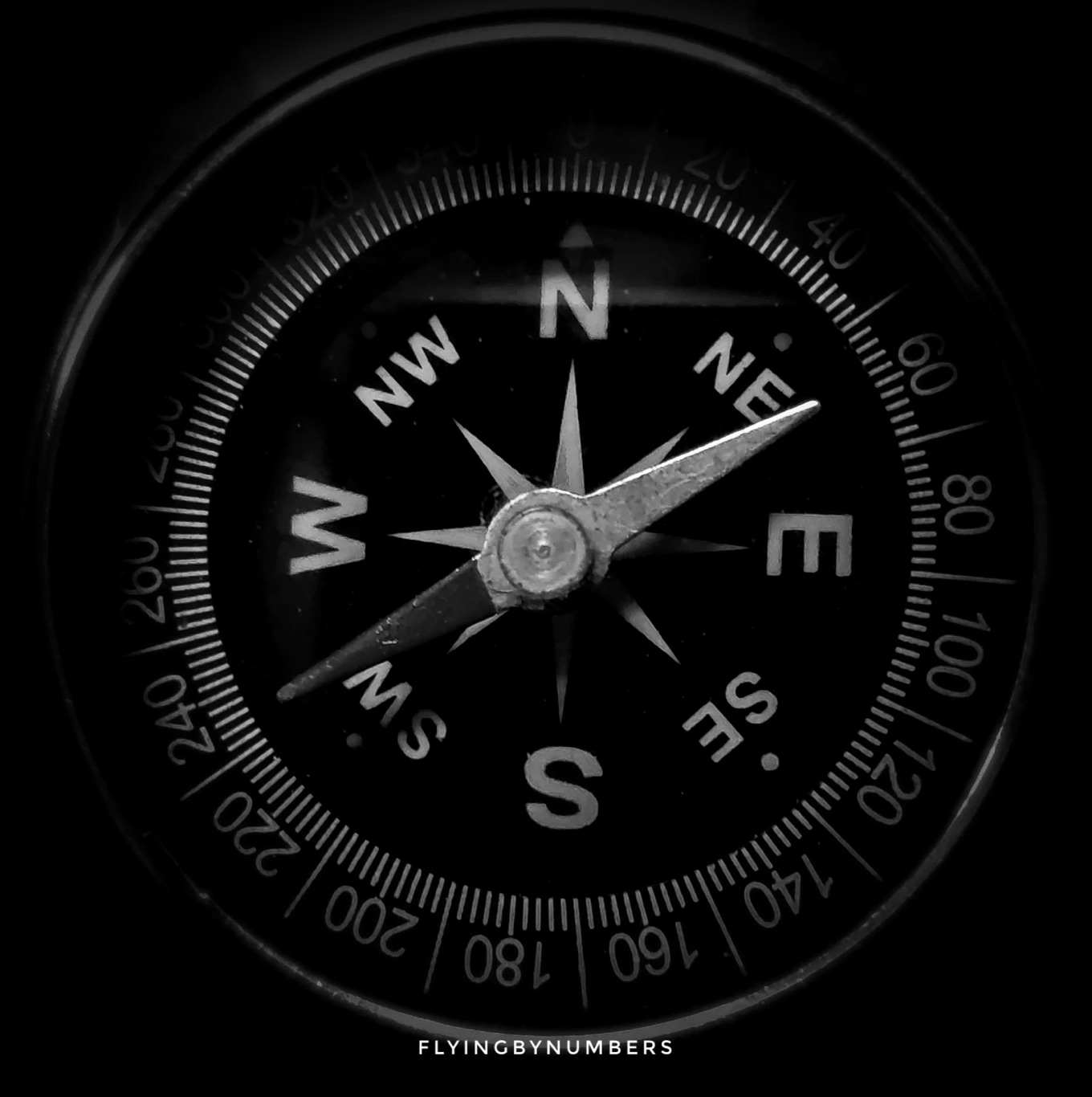

The North/South rule

One of the most basic rules of flight, the north-south or semicircular rules, dictate which altitude aircraft should fly at depending on their direction.

This ensures that aircraft, flying towards each other, criss-cross overhead with at least 1,000ft (ca. 305 m) of vertical separation between them.

Here’s a brief overview:

What if two aircraft are flying at the same level towards each other? This problem is solved by the north/south rule.

Aircraft flying on a heading between North and South (000-179 degrees) fly at an odd flight level (e.g. FL 350, FL 370, FL390)

Aircraft flying on a heading between South and North (180-359 degrees) fly at an even flight level (e.g. FL 360, FL 380, etc).

This ensures that aircraft flying towards each other in the same portion of sky, maintain an altitude difference of at least 1,000ft (ca. 305 m)

Procedural flying

At major international airports, pilots are heavily looked after by air traffic controllers. Constantly monitored, air traffic control guide pilots to and from the correct runways, and provide vectoring (heading and altitude) information, to avoid other aircraft in the area.

However, in many parts of the world where there is less air traffic control, procedural flying is used. This means that all movements are conducted without direct communication with ATC. So, how does it work?

Each airport publishes a Standard Instrument Departure (SID) or Standard Terminal Arrival Route (STAR).

These documents detail the exact procedures for entering and arriving into the airport’s airspace, which headings and altitudes aircraft should fly at to eventually line up with the runway — whilst avoiding other aircraft in the area.

Pilots will report overhead designated points in each procedure, and the air traffic controller listening (but not watching!) will understand exactly where each aircraft is during the procedure. Often using nothing more than a stopwatch and timing aircraft flying speeds, when there is a safe distance between arriving aircraft, the pilots will be cleared along the track to fly to the next reporting point.

It’s a labour-intensive, and comparably inefficient method to fly departures and approaches, but still plays a key role in keeping aircraft safe. Despite flying modern airliners, commercial pilots are still routinely tested on “back-to-basics” procedural flying in virtually every six-monthly simulator check.

How pilots avoid planes: The modern methods

As we’ve seen, old-fashioned methods such as the semi-circular rule and procedural flight paths do a good job of keeping aircraft separated — but they are rough guides and often labour intensive. Hasn’t technology moved on? For commercial aircraft, the answer is a resounding yes.

Today, there are two main tools that pilots use to avoid collision: Traffic Collision Avoidance System (TCAS) and Air traffic Control (ATC) radar.

TCAS

Traffic collision avoidance system (TCAS) is a form of airborne collision avoidance system (ACAS) designed to reduce the probability of mid-air collisions between aircraft.

TCAS enabled aircraft continuously broadcast their position via radio frequencies, similar to how ships use AIS. All other TCAS equipped aircraft in the vicinity continuously listen out for these broadcasts, and compare them to their position.

This comparison considers the speed and heading of both aircraft, and if it detects that a collision is imminent, it will direct the pilots of both aircraft to take evasive action. Some modern TCAS systems — such as in the latest Airbus A380 and A350 aircraft — will even automatically initiate a manoeuvre, which might be to climb, descend or level-off.

However, the “real” benefit to pilots is the enhanced awareness that TCAS systems provide. While pilots hope never to have to fly a real avoidance manoeuvre, modern systems are used on every single flight to display all the nearby aircraft and give the pilots an awareness of potential conflicts before they occur.

ATC Radar

Air traffic control (ATC) radar is the other main tool that pilots use to avoid collision.

In the busiest airspace, air traffic control use a combination of primary surveillance radar and secondary surveillance radar.

Primary surveillance radar (PSR) works by transmitting a microwave signal, which bounces off the aircraft and returns to the ground station. The time it takes for the signal to return is used to calculate the distance to the aircraft, while the direction it came from is used to determine the aircraft’s bearing.

Secondary surveillance radar (SSR) was developed to address the limitations of PSR. Instead of relying on a microwave signal being reflected off the aircraft, SSR uses a “pulse” transmission that is received by a transponder onboard the aircraft.

The transponder then responds to the interrogation by transmitting a signal back to the ground station that includes information such as the aircraft’s altitude, identification, and speed. This data is then used by air traffic controllers to provide separation between aircraft.

SSR can be used in all weather conditions and does not require line of sight, so it can be used to track aircraft flying behind hills or mountains. All modern commercial aircraft are required to be fitted with a transponder, and use an ATC assigned code It also offers the advantage of being able to track many more aircraft than PSR, making it the preferred radar system in busy airspace.

FAQs

How far apart do aircraft fly?

The minimum horizontal separation distance between aircraft in the cruise is typically 5 nm. Under radar control, within tightly regulated airspace such as major international airports, this distance can be reduced to as little as 3 nm.

For vertical separation, 2,000 ft is a standard seperation distance. However, with advancing technology, many busy sectors of airspace allow commercial aircraft to utilise reduced vertical separation minima (RVSM). Within this airspace, aircraft are only separated by 1,000 ft vertically.

When are planes closest together?

It might surprise you to know that the closest two commercial planes ever fly to each other is during takeoff and landing.

At the worlds busiest airports air traffic control have to maximise the rate of arriving and departing traffic, packing aircraft as closely together as possible. When there is good weather, busy airports typically do this by giving pilots “land after” clearances.

While aircraft initial arrive on final approach at around 3 nm separation, aircraft will “bunch up” when the preceding aircraft slows down during landing. As a result, some commercial aircraft are cleared to land with the aircraft in front only a few hundred metres ahead, and may only have a clear runway at as low as 100 ft.

Can commercial pilots see other planes?

The first rule is to keep a good lookout! Or so the saying goes… In fact, it’s only half true. For commercial airline pilots, ordinarily they will not be looking out of the window for other aircraft.

Summary

Pilots use a combination of different methods to avoid other aircraft, including automated TCAS systems, ATC radar guidance and by visually looking. While mid air collisions have always been very rare, the use of these tools has helped to further reduce the risk to a statistically insignificant level.

Looking out of the window to maintain visual seperation used to be a foundation for flying — and it’s still crucial for general aviation. However, with the advancement of air traffic control and the suite of technology available in many modern airliners, commercial pilots typically spend very little of their time visually avoiding other aircraft.

As a result, next time you’re onboard and wondering if that aircraft is too close for comfort, you can rest assured. Pilot’s no longer have to rely on “eyeballing” distances — they’ll know exactly the vertical and lateral separation between both aircraft!